All names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

| Written by Dot Lucci, Program Director at Aspire/MGH

Students diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may be the last group of students one would think of when thinking about teaching MESH (Mindsets, Essential Skills & Habits) or the first depending upon one’s perspective. For me, the answer to the question, “Can students diagnosed with ASD learn MESH?” is a resounding YES! Therefore, we must teach MESH to all students! MESH involves teaching children about the mindsets, essential skills and habits they need to succeed in school, work and life.

Given the diagnostic profile of ASD which includes deficits in socialization, theory of mind or perspective taking and behavioral challenges, MESH development may be considered a long shot. But, it isn’t. With the proper balance and instruction that caters to their learning style MESH can be taught to, synthesized and embodied by students with ASD. Philosophically, I believe that all students should be taught MESH. If MESH development can lead to positive results with students diagnosed with ASD then just imagine the potential impact it can have with typically developing children! Think about it…..wouldn’t it be wonderful for our future world if through MESH we could influence tomorrow by helping the children of today become adults who are mindful, compassionate, socially competent and skillful leaders.

Teaching MESH to students with ASD can and does influence their development in profound ways! Through our (Aspire/MGH) consultation to public schools across the state we are designing programs for students with ASD that include MESH instruction.

In our consultation work we focus on 3 primary areas that we call the 3S’s: self-awareness, stress management and social competency. Many adults with ASD have not reached their potential because they struggle in these areas. They don’t know who they are and “what makes them tick”, or that stress is a part of life. They may struggle with recognizing that getting along with and being kind and respectful to others is a part of life, even if you don’t agree with them. Many of these adults have advanced degrees but can’t get or keep a job. I’m simplifying the challenges they face and the 3Ss but you get the idea.

By highlighting the 3Ss in our work, we have witnessed significant growth and positive impact on student’s learning and ultimately their lives. By directly modeling and teaching these MESH skills, students diagnosed with ASD improve their understanding of self and other and their ability to manage stress and cope with adversity.

We also integrate MESH into how we teach them, harnessing their strengths in visual thinking and logical reasoning. We utilize a curriculum that we developed at Aspire/MGH called the Science of Me. Typically it is a class that is taught by a special educator. The Science of Me includes lessons on the brain and neuroanatomy, the physiology and biochemistry of stress and happiness, the mind-thoughts/feelings and their connection to behavior, among others. Also included are inventories of self-assessment (i.e. learning, sensory, personality style etc.), self-reflection, video analysis and biofeedback. By including science as the backbone of instruction, middle schoolers diagnosed with ASD improve their understanding of themselves, engage in more positive thinking, decrease the frequency of outbursts, demonstrate more positive social encounters with peers and are able to identify their personal triggers and self-calm.

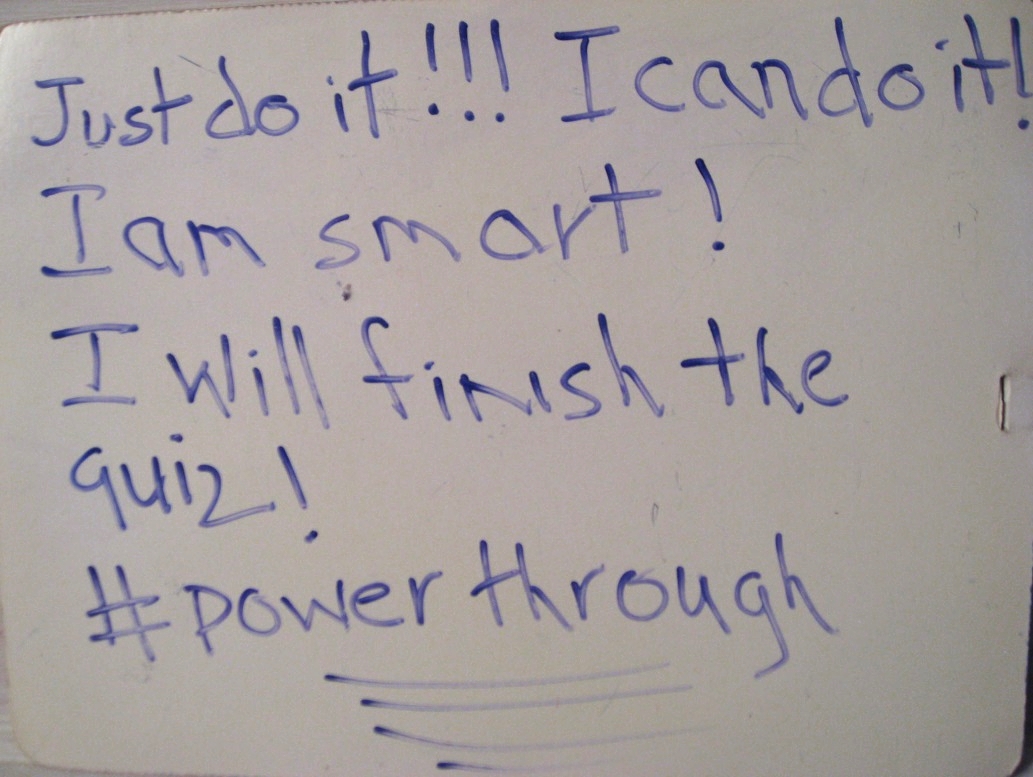

For instance, Matt, a seventh grader with a diagnosis of ASD, has many cognitive strengths, an above average IQ, and a great sense of humor but, in the past, he turned his peers off by being very blunt and direct in his communication style. He was also quite rigid in his thinking and exhibited a fair amount of anxiety. He was easily overwhelmed when confronted with any task or quiz that he perceived as challenging or unfair (even if the material was known to him and he was capable of doing it). Prior to building some MESH skills, he would call out negative comments and be disruptive in class, ultimately needing to be removed. However, over time, with direct instruction and self-awareness plans, he increased his understanding of himself and others. He improved his perspective taking capacity and discovered his communicative style was off-putting. His social relationships improved through Social Thinking™ instruction as he understood the need to keep those around him thinking positively about him. He also learned that he had certain stressors that triggered him such as the mention of a quiz/test. His anticipatory anxiety was palatable before quizzes, yet he was a capable student; so instruction included identifying his mindset as fixed and that showing him that data didn’t support his belief about himself. Prior to instruction in these MESH areas, he would need to leave the classroom as his anxiety escalated and his behavior became disruptive. After a few months of working on these skills, he was capable of recognizing his trigger and knew to politely ask to leave the room. Once in the break room he utilized materials in his personal binder including some on being an optimist vs. pessimist, the effects of dopamine increase (which had photos of pleasant experiences), and stress management techniques. After resetting himself to a positive frame of mind and engaging in self-calming strategies he wrote this:

Then he took a few more deep breaths, re-entered the classroom, took the quiz and ultimately obtained a grade of 83. Matthew’s growth in key MESH skills is evident.

Students diagnosed with ASD who have average to above average cognition and who are fully included in general education classes need MESH instruction so they are able to access their full potential. Often times these students, like Matthew challenge teachers and administrators because of their aberrant behavior, blunt and honest communication style, rigid thinking and lack of social understanding. Given the high cognitive capacity of many of these students, there is great potential for them to mature into adults who could make a difference in our world. However, many of them lack the key skills to do so. Sadly many never reach their potential as challenges impede their progress. Therefore, it is critical that we prioritize the teaching of and embedding of MESH as part of every student’s curriculum. To learn more about the Aspire program at Massachusetts General Hospital visit: www.mghaspire.org

Lucci, D., Levine, M. Challen-Wittmer, K. & McLeod, D.S. (2014). Technologies to support interventions for social-emotional intelligence, self-awareness, personal style and self-regulation. In Bosner, K., Goodwin, M.S., & Wayland, S.C.(Eds.) Technology for Students with Autism: Innovations that Enhance Independence and Learning (201-226). Paul H. Brookes. Baltimore, MD.